|

|

The Ronne Family

"Antarctica's

First Lady" - newly released autobiography by Edith M. "Jackie"

Ronne "Antarctica's

First Lady" - newly released autobiography by Edith M. "Jackie"

Ronne

Biography

from Encyclopedias Online

80th Birthday Tribute by

daughter, Karen Ronne Tupek

Memories, Frozen in Time

- article in Washington

Post, March 1995, about Jackie's return to Stonington Island, Antarctica.

Alternate Bios

Society of Woman Geographers Bio

Adventures of the Elements

- Jackie featured as a hero on a game card

Jackie Among the Icebergs

- article by Georgia Tasker about Antarctic trip with Jackie

At Stonington Island, Antarctica in 1947 and

in 1995.

Edith Anna Maslin "Jackie" Ronne

Briefly:

Born: October 13, 1919;

Baltimore, Maryland

Edith "Jackie" Ronne was a

U.S. explorer of

Antarctica.

She married

Finn Ronne on

March 18,

1941. On the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition of

1946 -

1948, that her husband commanded, she became the 1st

American woman to set foot in Antarctica, and with Jennie Darlington, the wife

of the expedition's chief pilot, became the first women to overwinter in

Antarctica. They spent 15 months together with 21 other members of the

expedition in a small station they had set up on

Stonington Island in

Marguerite Bay. She married

Finn Ronne on

March 18,

1941. On the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition of

1946 -

1948, that her husband commanded, she became the 1st

American woman to set foot in Antarctica, and with Jennie Darlington, the wife

of the expedition's chief pilot, became the first women to overwinter in

Antarctica. They spent 15 months together with 21 other members of the

expedition in a small station they had set up on

Stonington Island in

Marguerite Bay.

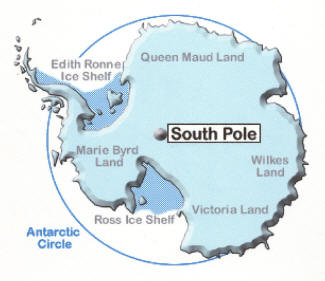

She is the namesake of the Ronne Ice Shelf, which was previously called Edith Ronne

Land. Her husband, Finn, who discovered and mapped that previously

unknown territory during his Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (1946-8),

named it in her honor.

Edith Ronne returned several times to Antarctica, including on a

Navy-sponsored flight to the

South Pole in

1971 to commemorate the 60th anniversary of

Roald Amundsen first reaching the South Pole (she was the seventh

woman at the pole), and a

1995 trip back to her former base at Stonington Island as guest

lecturer on the expedition

cruise ship Explorer.

Shorter Bio -

150 Words:

Jackie Ronne, a fellow of the Explorer’s Club, was

the first American woman to set foot on the Antarctic continent and the

first woman to over-winter as a working member of an expedition. She

married Norwegian-American Antarctic explorer, Captain Finn Ronne, and he

persuaded her to join his 15-month Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition,

1946 – 48 on Stonington Island in Marguerite Bay. She helped with

scientific experiments, kept the expedition’s log and wrote many articles

for newspapers back home, documenting the discovery and mapping of the

world’s last unknown coastline in the Weddell Sea. Her husband named the

new territory Edith Ronne Land to honor her; it was later changed to Ronne

Ice Shelf, the world’s second largest. She continued to write and lecture

about the Antarctic, including in encyclopedias and her recent book,

Antarctica’s First Lady. She returned to Antarctica 15 more

times, including a visit to the South Pole. Jackie Ronne, a fellow of the Explorer’s Club, was

the first American woman to set foot on the Antarctic continent and the

first woman to over-winter as a working member of an expedition. She

married Norwegian-American Antarctic explorer, Captain Finn Ronne, and he

persuaded her to join his 15-month Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition,

1946 – 48 on Stonington Island in Marguerite Bay. She helped with

scientific experiments, kept the expedition’s log and wrote many articles

for newspapers back home, documenting the discovery and mapping of the

world’s last unknown coastline in the Weddell Sea. Her husband named the

new territory Edith Ronne Land to honor her; it was later changed to Ronne

Ice Shelf, the world’s second largest. She continued to write and lecture

about the Antarctic, including in encyclopedias and her recent book,

Antarctica’s First Lady. She returned to Antarctica 15 more

times, including a visit to the South Pole.

Edith Anna "Jackie" Maslin Ronne: a biography

Born Edith Ann Maslin on October 13, 1919, Edith "Jackie" Ronne

was raised in a conservative, private Baltimore family. Her father,

Charles Jackson Maslin, worked several jobs, his last being with the B&O

Railroad. Her mother, Elizabeth Parlett Maslin, could have taught school,

but like a proper married woman of her day, she stayed home instead and

reviewed Edith's homework every night making sure she never went to school

without knowing her lessons letter perfect.

According to Edith, she spent three "marvelous" summers

away from home at a Girl Scout summer camp, Camp May Flather, in Virginia.

It was at camp where she acquired her nickname, "Jackie." In the 1930s,

Baltimore, Maryland, did not believe in co-education in their public

schools so she graduated from Eastern High School at sixteen without ever

having a date, except when she arranged for a classmate's brother to take

her to the senior prom.

Jackie spent her first two years in college at the College

of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. Then she transferred to George Washington

University in Washington, D.C., In order to be near the university, Jackie

moved to live with her aunt and uncle in Chevy Chase, Maryland, who were

financing her education. The first person she recognized on campus was a

girl from Girl Scout Camp. To her friends, she introduced Edith as Jackie,

and everyone felt the name better fit her personality than Edith. Since

that time she has been called Jackie.

At George Washington University, Jackie joined Phi Mu Sorority, had a

great social life, and in 1940 graduated with a major in History and a

minor in English. When she graduated, it was not easy to find a job with a

"mere" undergraduate degree. Therefore, Jackie began a typing and

shorthand course while looking for work. The National Geographic Society

offered her a job. After about nine months, she sought and found a

government job at the Civil Service Commission paying twice the salary of

the National Geographic Society. A few months later she moved on to the

State Department where she would remain for over five years serving in

several different positions from file clerk to International Information

Specialist in the Near and Far Eastern Division of Cultural Affairs.

In 1942, she met the polar explorer Lieutenant Finn Ronne (who would

later advance to the rank of Commander) on a blind date and over the

ensuing months, Jackie enjoyed his maturity (Finn was 20 years her

senior), nationality, "charming" Norwegian accent, and stories of

exploration. Finn proposed to Jackie before Christmas of 1943 and they

were married on March 18, 1944.

Finn Ronne was a great organizer, planner, and leader; and in 1947 he

commanded the last privately funded expedition to Antarctica despite

roadblocks and obstacles erected by Admiral Byrd and associates and the

British who currently occupied the area of Antarctica where the Ronne

Expedition was destined. (Once the Ronne Expedition reached the frozen

continent, the Americans and British worked closely together.)

Nevertheless, regardless of a small budget and crew, the Ronne Antarctic

Research Expedition

departed on January 25, 1947, from Beaumont, Texas, where Finn selected

Beaumont Eagle Scout Arthur Owen to join the expedition. Jackie edited all

of Finn's correspondences and reports and was to be in charge of the

domestic side of the expedition. However, instead of remaining stateside,

she resigned her position with the State Department to accompany her

husband on his fifteen month

Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition.

As Expedition Recorder-Historian, Jackie Ronne wrote the news releases

for the North American Newspaper Alliance. She also kept a daily history

of the expedition's accomplishments, which formed the basis for her

husband's book, Antarctic Conquest, published by Putnam in 1949, and made

routine daily seismographic and tidal observations when the geophysicist

was in the field during summer trail program.

Jackie Ronne became the first American woman to set foot on the

Antarctic Continent. (Before her, only the wife of a Norwegian whaling

captain had done so very briefly.) Mrs. Ronne, along with the wife of one

of the expedition's pilots, became the first two members of an

over-wintering expedition, and the first women to spend a year in the

Antarctic. No woman had ever lived in the Antarctic before this, nor did

any do so for the following twenty-five years, until women scientists

occasionally accompanied their scientific husbands in recent years. The

400,000-square-mile area newly discovered by the Ronne Antarctic Research

Expedition was named EDITH RONNE LAND by the U.S. Board on Geographic

Names, making it one of the very few land areas honoring a woman of

non-royal birth. After 20 years on the maps, the feature was renamed RONNE

ICE SHELF, an area which is second only to the great Ross Ice Shelf.

In the years following that first expedition, Jackie Ronne has lectured

extensively throughout the U.S. and in numerous foreign countries. In

addition to collaborating with her husband in various scientific and

popular accounts, she has written numerous articles including those for

the annual editions of the Britannica, Americana, and Funk and Wagnall's

encyclopedias, as well as many articles for the North American newspaper

Alliance. In the years following that first expedition, Jackie Ronne has lectured

extensively throughout the U.S. and in numerous foreign countries. In

addition to collaborating with her husband in various scientific and

popular accounts, she has written numerous articles including those for

the annual editions of the Britannica, Americana, and Funk and Wagnall's

encyclopedias, as well as many articles for the North American newspaper

Alliance.

Upon the invitation and sponsorship of the Argentine Government in

1959, she participated in the first commercial tourist cruise to

Antarctica.

In 1962, she made a trip to the Arctic Islands of Spitsbergen,

visiting Norwegian and Russian coal mining stations on a Norwegian sealing

vessel which penetrated the pack ice to within 600 miles of the North

Pole. In 1962, she made a trip to the Arctic Islands of Spitsbergen,

visiting Norwegian and Russian coal mining stations on a Norwegian sealing

vessel which penetrated the pack ice to within 600 miles of the North

Pole.

In 1971, upon the invitation of the Secretary of Defense, she

accompanied her husband as a guest of the U.S. Navy to McMurdo Sound,

Antarctica, and made a flight to the South Pole Station, as the first

husband and wife team and only the eighth woman to do so, in observance of

the 60th Anniversary of Amundsen's attainment of the Pole on December 14,

1911. (Finn Ronne's father, Martin Ronne, was a member of the Amundsen expedition.) In 1971, upon the invitation of the Secretary of Defense, she

accompanied her husband as a guest of the U.S. Navy to McMurdo Sound,

Antarctica, and made a flight to the South Pole Station, as the first

husband and wife team and only the eighth woman to do so, in observance of

the 60th Anniversary of Amundsen's attainment of the Pole on December 14,

1911. (Finn Ronne's father, Martin Ronne, was a member of the Amundsen expedition.)

In

addition, Jackie held various offices in the Society of Woman Geographers;

The Columbian Women of George Washington University; the United Nations

Association and the National Society of Arts and Letters. She assisted in

civic organizational work in various capacities and is listed in Who's Who

of American Women. Jackie received a special Congressional Medal for

American Antarctic Exploration, was elected president of the Society of

Woman Geographers, holding that office from April 1978-1981. She was the

recipient of a special Achievement Award from Columbian College of George

Washington University and dedicated a Polar Section to the National Naval

Museum. In

addition, Jackie held various offices in the Society of Woman Geographers;

The Columbian Women of George Washington University; the United Nations

Association and the National Society of Arts and Letters. She assisted in

civic organizational work in various capacities and is listed in Who's Who

of American Women. Jackie received a special Congressional Medal for

American Antarctic Exploration, was elected president of the Society of

Woman Geographers, holding that office from April 1978-1981. She was the

recipient of a special Achievement Award from Columbian College of George

Washington University and dedicated a Polar Section to the National Naval

Museum.

She

was a special Guest Lecturer aboard Abercrombie and Kent's Antarctic

Cruise Ship, "Explorer," in February and March, 1995, when she

returned to her former Antarctica base at Stonington Island as a guest

lecturer. and aboard the

Orient Lines ship, "Marco Polo," in January and February, 1996,

and again in 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, and 2002. In her lifetime, she has made 16 trips to Antarctica. She

was a special Guest Lecturer aboard Abercrombie and Kent's Antarctic

Cruise Ship, "Explorer," in February and March, 1995, when she

returned to her former Antarctica base at Stonington Island as a guest

lecturer. and aboard the

Orient Lines ship, "Marco Polo," in January and February, 1996,

and again in 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, and 2002. In her lifetime, she has made 16 trips to Antarctica.

Jackie Ronne has one daughter, Karen Ronne Tupek,

and two grandchildren. Both her daughter and granddaughter were also Girl

Scouts. Her grandson was a very active Scout and engineering student (like his grandfather Finn Ronne, who

was a mechanical engineer with postgraduate studies in naval architecture)

and excelled in rowing, making the U.S. Junior National Rowing Team in

2001, and anchoring the Varsity boat at the University of Wisconsin.

Currently, Jackie Ronne resides in Bethesda, Maryland, and is as active

and quick-witted as ever. She returned to Beaumont, Texas, on November 11,

2004, for the opening of the Ronne Expedition and Arthur Owen Museum

Exhibit at the Clifton Steamboat Museum, the debut of her book

"Antarctica's First Lady," a reunion of the surviving six crew members

from the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition, and the unveiling of her

Adventures of the Elements character card, the Jackie Ronne card. These

events to honor Jackie Ronne, the Arthur Owen family, and the expedition

are being coordinated by Three Rivers Council #578, Boy Scouts of America,

which is the same Boy Scout Council area that was involved in the 1947

expedition. Philanthropist, historian, and Clifton Steamboat Museum owner

David Hearn, Jr., has made this historically significant event possible by

funding the publication of her book and the extensive Ronne Exhibit at his

museum including digitizing and preserving over 16,000 feet of motion

picture film from the expedition.

80th Birthday Tribute

Written by daughter Karen Ronne Tupek and read

at her 80th birthday party, with theme "Cruise

to Antarctica": October 13, 1999, Bethesda, Maryland Written by daughter Karen Ronne Tupek and read

at her 80th birthday party, with theme "Cruise

to Antarctica": October 13, 1999, Bethesda, Maryland

As Cruise Director, I want to welcome

everyone here tonight to our “Cruise to Antarctica”. In fact, we are

cruising there, right now. Look closely at the icebergs off our bow,

here, with a penguin, as well. And, there’s the Lemaire Channel, over

there, with its most spectacular scenery. And we seem to have a pesky,

but friendly penguin in our midst who has gotten lost from the Rookery.

Perhaps he’s looking for some Krill. Come on over here, Penny. Everyone

say “Hi” to Penny.

I’m glad you could join us on this

special Antarctic cruise, celebrating the 80th birthday of my

mother. Now, Mom, you know you couldn’t escape having a party. And, we

have to have a little “recap” of the last 80 years, so Mom, this is your

life.

My mother is a great woman, not only

because she is my mother, and a most devoted and loving mother, at that.

But also because she is the First Lady of the Antarctic.

First Lady of the Antarctic - That title

has many components, as she is first and foremost, a lady, with many

charms - as well as social graces and a vivid personality - that have

allowed her to sparkle across the globe, from the places of common men to

the palaces of royalty. But secondly, she is a first, a pioneer. As the

first American woman to set foot on the Antarctic continent, she is also

the first woman in the world to be a working member of an Antarctic

expedition and to winter-over on the frozen continent. She firmly has her

place in Antarctic history.

As a result, her pioneering achievement

has accorded her a rare honor for a woman of non-royal birth: Antarctica’s

Ronne Ice Shelf, the world’s second largest, is named for her.

Mom was born and raised amidst the marbled

front steps of Baltimore as Edith Anna (she hates that) Maslin. She got

the nickname of Jackie, taken from her father’s middle name of Jackson, at

Camp Mayflather, a Girl Scout camp in Virginia. It was long forgotten

until she encountered a former scout friend on her first day at college

here in Washington. Introduced around campus with her old Girl Scout

moniker, the nickname “Jackie” stuck with her ever-widening social group.

When Mom, having skipped two grades,

graduated from Baltimore’s Eastern High School at the tender age of 16,

she kissed Baltimore “good-bye” with a “farewell” “good riddance” “au

revoir” “adios” “sayonara” and “I’m outta here”. (Did you catch that?

She hated Baltimore!) She came to Washington to live with her aunt and

uncle, and was exposed to a wider view of life. She flourished while

living with them in Chevy Chase. Auntie and Uncle, as I called them,

later became the grandparent figures in my life.

“Auntie” sent her to Wooster College in

Ohio for two years. While there, she really tried hard to major in boys.

But when the college wouldn’t award that degree, she transferred to George

Washington University and eventually joined Phi Mu sorority. She

graduated from GW at the young age of 20 with a degree in history, which

is ironic, since she ended up making some history of her own in the

Antarctic.

She worked briefly for the National

Geographic Society, then the State Department, where she befriended, among

others, my Godmother, and that changed her life.

She met my Norwegian father, Finn Ronne,

on a blind date arranged by my Godmother, Bettie Earle Heckmann. Bettie

paired them up, despite a 20-year age difference, because they both

skied. Now, my father had already ski-jumped off of every small mountain

in Norway, skied glaciers and miles of snowfields, and guided sledges

behind dog teams in the Antarctic. And my mother’s skiing consisted of

sliding down the hill behind the Shoreham Hotel into Rock Creek Park.

Their skiing conversation was over in a matter of minutes, but fortunately

they found more things in common. When told that my father was agile for

his age and could do deep knee bends, my mother’s friend said, “On the

dance floor? How terrible for Jackie!” Well, my father was very

athletic, and indeed they went to Stowe, Vermont, to ski on their

honeymoon. Mom should have guessed what was coming, what with all that

romantic honeymoon snow.

Shortly after their marriage in March of

1944, my father planned his own private expedition to the Antarctic, his

third over-wintering experience, to conduct scientific investigations and

to discover and chart new lands. The Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition

finally got going after the end of WW-II and departed the end of 1946.

When my father needed her assistance, he gradually persuaded Mom to go

along on the expedition, rather than assist from afar in Washington. As

she sailed further and further south to help with last minute

preparations, she was also grabbing more and more last minute supplies as

her fate was becoming clearer and clearer. Her horrified aunt cautioned

in the last paragraph of her last letter attempting to dissuade Mom from

going, “And don’t forget, the cold will ruin your complexion.” So off she

went, having started the journey with only a cocktail dress, nylon

stockings, and high-heeled shoes, – to become a pioneer of women in

the Antarctic.

Mom handled the daily logs of the

expedition, wrote newspaper articles for the North American Newspaper

Alliance, kept the official expedition diary, and assisted in many

scientific experiments.

The experience made her life and opened

doors she never imaged. Upon her return in 1948, she was a bit of a world

celebrity and toured the U.S. on a lecture tour, pinch-hitting for my

father. Over the years, she helped write and edit my father’s four

books. Articles, TV appearances, and honors followed.

She went on the very first tourist cruise,

by the Argentines, to the Antarctic in 1957, and was later flown, along

with my father, to the South Pole in 1971, the first couple to be there,

to commemorate Amundsen’s 60th anniversary of attaining the

South Pole. In addition, she was the seventh woman to stand at the South

Pole; the first six were journalists who together jumped from an airplane,

so none could claim being “first”.

As for achievement on her own, she served

for three years as international president of the Society of Woman

Geographers, wrote the annual articles on the Antarctic for the

Encyclopedia Britannica for many years, and continued to give lectures.

In addition to SWG, she continues to be an active member of the Washington

Chapter of the National Society of Arts and Letters, ARCS, and the

Explorer’s Club.

And speaking of exploring, she’s always

had the travel bug. In fact, travel has been a major theme of her life.

When I was a kid, for many years running we spent lots of time with the

Sweeney family - skiing at Aspen, and sailing at Gibson Island in the

Chesapeake Bay. Also, we traveled twice all over Europe, once ending up

at Spitzbergen in the Arctic, even pushing back the Iron Curtain there

with a landmark visit to a Russian Base. And of course we’ve spent lots of

time in my father’s homeland of Norway on four or five different trips.

We also made an extensive trip to Mexico. During my summer camp years,

Mom and Dad left me behind when they were brought to Japan by the

government to advise some mountain climbers about equipment for scaling

high peaks in the Antarctic.

Since my father’s death in 1980, she has

forged trails to New Zealand, Australia, Alaska, and Western Canada. As a

result of her most famous trip, Mom was the subject of gossip on

Washington radio. She traveled through China with WMAL radio

personalities Harden and Weaver, and became known as the “shop-a-holic”!

“Wow, Jackie really cleaned out the tourist shops! She looked like a

heavily laden Christmas tree getting off the airplane!” “Yeah, that

Jackie Ronne really knows how to shop!” were Harden and Weaver’s comments

during their show’s morning broadcast. But later, she did have a featured

live interview with them on their show.

While I was in college, Mom and I made a

long 8-week road trip all through the western states, stopping in the

National Parks as well as glamorous cities. We hiked and climbed hills in

the parks and were wined and dined in royal style at Caesar’s Palace in

Las Vegas. Her favorite part was the scenic drive along the rocky

California coast; so much so, in fact, that we backtracked and drove it

three times. We even tried swimming in the Great Salt Lake – big

mistake. It was so salty that it was more like floating. We ended up in

the northern parks, and took in the scenery of the Tetons, Yellowstone,

and Mount Rushmore. That long odyssey was a blast!

When I was free of school, Mom and I

continued to travel and we investigated Spain, Mallorca, the Greek Isles,

and Turkey. In 1987, Mom asserted her independence and did

something that my father always wanted to do, but never did: she bought a

condo in Florida. It has been her refuge and has become our family's

second home, and a jumping-off place for more travel.

Once I married, Mom, Al, and I, and later the kids,

continued to make numerous trips to the Caribbean, out west again, Norway

again, and the ultimate trip, Antarctica – three times for me and . . .

how many times is it for you, Mom? And I’m hoping for many more

adventurous expeditions with her.

She has now gotten on the Antarctic cruise lecture

circuit and made trips as a lecturer the past five years, and continues as

a celebrity fixture on the Marco Polo, on which our whole family has had

the pleasure of cruising to the continent of our heritage. She

is scheduled to take three more trips this year on the “Marco Polo” to

Antarctica.

Mom’s traveling days came to a brief halt

in 1951, when she gave birth to her only child, me. I was most fortunate

to have her as my mother all these years. She was the one to sit up late

at night with me when I was sick, wake me up early in the morning for

school with breakfast on the table, chauffeur me to every sort of activity

imaginable, attend every one of my school performances, and talk late into

the night about school dances or my latest crushes on boys. And during

college, she sent me the best “care packages”; most notable was this

crazy-fangled hammer that doubled as several other tools, for my

architecture class – but it saved the day!

She has always been loving, nurturing,

even-tempered, and accepting of me and everything I’ve done. Most every

child says their mother is the best, but I’ll say that she really is

the best because she is always there, always available as a

mother.

As a grandmother, she has not only been a

loyal babysitter to help out Al and me, but she has been a constant

stabilizing support to her pride and joys, grandson Michael and

granddaughter Jackie, who is obviously named after her.

Everyone comments to me about how

wonderfully warm, open, and especially charming my mother is. She is easy

to talk to and confide in, and it’s always so interesting to hear her

stories. Even stories I’ve heard a million times are fun to hear again,

because of the enthusiastic way in which she tells them. Now, if she

could only get those stories published and out in print for everyone to

read in book form, that would be a big goal accomplished!

Mom is a loyal friend and goes out of her

way to try to do favors for other people, if she can. She gets involved

in people’s lives in creative and meaningful ways.

As my father said, “I never thought I

would ever be 80! It’s not that I wouldn’t live that long, but I never

thought the day would actually come.” But for Mom, so it has, and I am so

glad that everyone is here to share in her celebration, not only of her

milestone year, but in our celebration of her as a wonderful, beloved

person. All of our lives are enriched by this woman – my mother – Jackie

Ronne.

Edith "Jackie" Ronne

(Mrs. Finn Ronne)

Member of the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition, 1946-48

"Roald Amundsen should see us now," I said to

my husband in December of 1971, as we settled into the bucket seats of the

Hercules C-130 turbo jet flying us to the South Pole. Once, the Norwegian

explorer had driven his dog teams across the Ross Ice Shelf, over perilous

crevasses, up steep glaciers to the 10,000 foot high polar plateau. It

took Amundsen's party two months of difficult sledging to reach the South

Pole on December 14, 1911. Now, sixty years later, we retraced the route

in three hours - about and hour and a half of flight time for each month

of their tortuous struggle.

Although the round trip from McMurdo Sound on

Antarctica's icy coast to the geographical South Pole can be achieved by

air in one good flying day, women who have made the trip are more scarce

than penguin chicks at a zoo. Many women have crossed the Antarctic Circle

via tourist ships in recent years, but you can count in an ice tray those

who have contributed to on-the-spot history of the Continent. The pristine

icy scenery we were surveying from the relative warmth and safety of the

huge ski-equipped Navy plane's cockpit was not new to me. It was my third

venture to the Antarctic Continent, although my first directly to 90

degrees South, where all the meridians meet.

When my husband, Captain Finn Ronne, first

organized the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition in 1946, I readily gave

a helping hand to the enormous amount of tedious planning such an

undertaking required. So familiar had I become with the background of the

expedition, that it had been my intention to handle its affairs Stateside,

while they were away. It was a hectic departure, and while bidding my

husband good-bye, he asked if I would go with his ship as far as Panama to

help with the last minute details. My two week leave of absence from a

challenging State Department position was hastily extended. (Actually, I

never did return to it.) My suitcase contained little more than a good

suit, a good dress, nylon stockings and high heeled shoes. Little did I

realize this was the beginning of a series of events that led me to be the

first American woman to set foot on the earth's seventh Continent and to

spend my third and fourth wedding anniversaries there.

Not only did my husband ultimately persuade me

to accompany the expedition as Historian and Correspondent for the North

American Newspaper Alliance, but he permitted the wife of one of the other

members to go, so as to quell any qualms I had about becoming the "first

and only". We selected the most appropriate size clothing from the large

supply sent with us from the Quartermaster Corps for cold weather testing.

Although I had lived through previous

Antarctic adventures vicariously since first meeting my explorer husband,

I was completely unprepared for the truly magnificent scenery of that

desolated southern continent. Once within the Antarctic Circle, our 183

foot, wooden hull ship slowly made her way through the light pack-ice belt

that surrounds the Continent at all times. Under the brilliant sun, the

shimmering icebergs and the snowcapped mountain peaks stood in great

contrast to the vivid blue sky and cobalt sea. Heavily crevassed glaciers

descended through the majestic mountain passes ending in a 200 foot high

frozen ice shelf which, with few exceptions, encircles the 5,200,000

square mile land mass.

Once our ship was securely anchored in a cove

off Stonington Island, sheltered by a curving glacier in Marguerite Bay,

we began transporting scientific equipment, food for two years, dogs,

three airplanes, gasoline, 30 tons of coal and innumerable other materials

ashore. Within weeks, the specially constructed and insulated buildings

were ready for occupancy and we moved in. Meanwhile, ice had formed

around the ship and soon she was intentionally frozen-in for the winter.

With my husband, I shared a small hut, about twelve feet square, connected

to the mess hall bunk house by a short tunnel.

During the long winter night that soon come

upon us, I learned first hand of the tedious hard work required to carry

on investigations in twelve branches of science under harsh polar

conditions. Later, I assisted our geophysicist in some of his routine work

while he was away from the base. Meticulous preparations also were

necessary for the aerial exploratory programs and surface geographical

survey teams planned upon the sun's return. Usually, I wrote an average of

three articles a week describing our progress for radio transmittal to the

N.Y. Times receiving station. For relaxation, we had motion pictures

several times a week. Classical and modern music could be heard throughout

the isolated camp most any hour of the day. There were, of course, endless

discussions on all imaginable subjects, as well as an occasional card

game, however, when all the candy bars had been won, the men ceased

playing poker. But the library with its great variety of subject matter

most appealed to me. Thus, the winter night passed quickly. Even so, all

hands were certainly glad when the sun's rays finally returned to the

northern horizon and the men were able to tackle their outside

investigation.

With my husband as navigator, his carefully

planned flights gradually discovered new land and mountain ranges far

south in previously unknown areas. Months later, upon our return, the U.S.

Board of Geographic Names called the newly discovered area, which was

about the size of the state of Texas, EDITH RONNE LAND. It remained on the

maps for twenty years, until the Board again decided to name the second

largest ice shelf in the world the RONNE ICE SHELF for all three Ronnes,

each of whom had spent more than a year in Antarctica.

Martin Ronne, my husband's father, had been a

member of Amundsen's expedition. He made the small tent Amundsen left at

the South Pole signifying his December 14-17 arrival. Martin remained with

Amundsen through twenty years of polar exploration and subsequently became

the only member of Admiral Richard Byrd's first expedition who had ever

been to Antarctica before. Upon Martin's death in 1931, his son, Finn

Ronne, immediately followed in his father's footsteps as a natural

extension of his Norwegian heritage.

In recognition of our family's long

involvement in Antarctic exploration, my husband and I were invited by the

Department of Defense on a flight to the Pole in December 1971, in

remembrance of Amundsen's 60th anniversary of his reaching the Pole. This

was my husband's ninth (and last) journey south over a 38 year span,

including four over-winterings of 15 or more months duration. To our

knowledge at that time, Finn Ronne had sledged more miles behind a dog

team

than any other man and was well aware of the grueling effort involved in

advancing Antarctica's frontiers.

Below us, the polar bound tracks of Amundsen,

Scott, and Shackleton had long since been obliterated by the shifting

winds. Not only were we on our way to pay homage to the remarkable feats

of willpower, stamina, and courage of these early pioneers, but we

intended to observe the great progress that had taken place since.

The majestic and terrifying beauty of the

Beardmore Glacier defies description. Bordered on either side by high

mountains, this wide flowing frozen river moves its ice masses from the

high polar plateau precipitously down to the Ross Ice Shelf. As we flew

southward, numerous dense crevassed areas disrupting its surface could be

seen from the safety of our vantage position in the cockpit of the plane.

With brilliant sky overhead and only a few scattered clouds on the distant

horizon, the sharp ridges and black rock outcrops stood in distinct

contrast to the dramatic ice panorama of our flight track below.

Continuously, we climbed up the steep glacier, so formidable to the early

explorers, until we reached the edge of the 10,000 foot high polar

plateau. An eternally white virgin surface stretched as far as the eye

could see. For the next 200 miles we scanned the endlessly white horizon

for the Pole Station. Finally, we spotted movement on the distant snowy

surface where men were preparing for our arrival. Soon we were on the

ground at 90 DEGREES SOUTH!

It was bitterly cold! We noticed it at once,

particularly on our faces. The chill factor was 80 degrees below 0,

Fahrenheit, although the temperature was a mere minus 20. We marveled at

those who had made it the hard way. Never could we know the feeling of

those intrepid men who had endured so much hardship and incredible

sacrifice. For us it had been spectacular and embarrassingly easy.

Newcomers are ushered directly to the Pole, a

few yards from the makeshift runway. We had just become the first husband

and wife team to set foot there. I was the seventh woman to stand at the

pole, the first six being woman journalists who jumped simultaneously from

the airplane together during the command of Admiral George Dufek in the

late 1950's. The South Pole is about ten feet high and decorated like a

barber pole. It is surrounded by the fluttering flags of the sixteen

signatory nations to the 1959 Antarctic Treaty. The treaty "froze"

national claims and opened the Continent to science and peaceful purposes

only. As we staved off frostbite, the photographers recorded my husband's

presentation to Deep Freeze's commanding officer, Admiral Leo McCuddin, of

two historic photographs, one of Amundsen in December 1911 and one of

Scott a month later, both at the Pole.

Hurriedly, we ducked into the entrance of our

Amundsen-Scott base and carefully descended the chiseled icy steps to

buildings and their connecting tunnels buried some twenty feet beneath the

surface. As we toured the station, the various scientific research

programs came alive. Geological, biological and upper atmospheric

information is being systematically inventoried at all of our Antarctic

bases, along with similar occurrences in other area of the world. Some

immediate applications of the results already obtained provide us with

more accurate predictions in long-range radio transmission and weather

forecasting, not to mention some legal and political problems connected

with the already known mineralization of the continent. In a somewhat

lighter vain, a fascinating three year study of the sleep and dream

patterns of personnel was being conducted to help understand human

adaptation to isolation.

Our stay at the Pole station was concluded

with a leisurely meal of steak, cafeteria style, after which we made a

short-wave radio broadcast to Lowell Thomas, a friend of many years. The

three and a half hour flight back to McMurdo (our main U.S. staging area)

was uneventful, but for me the day will remain forever the most memorable

of my life.

The next morning we flew to Cape Royds. We

intended to spend only an hour or so at the hut used in 1907, by British

leader Sir Ernest Shackleton when his party attempted to sledge to the

Pole by manhauling their heavy loads. They came within 97 miles of their

hard fought goal before adverse conditions forced them to turn back. It

would have been impossible for them to have reached the Pole and return

alive.

After viewing the austere conditions of a

polar camp from yesteryear and photographing many nesting penguins in a

nearby rookery, we climbed into the two UH-1N helicopters and strapped

down for takeoff. Suddenly, our previous 20 mile visibility changed so

rapidly that after five miles of flight we ran into whiteout conditions.

There was no visible horizon and no depth perception. Sea ice, glaciers

and sky all appeared as one and made us feel as though we were maneuvering

in a bottle of milk. As both helicopters swung around, they informed

Ground Control at McMurdo that we were returning to Cape Royds. I was a

lone woman with seventeen men at Shackleton Base and we were marooned!

Also, we were hungry, tired and generally

uncomfortable. Soon the efficient crew brought out their only survival

gear and lit a small gasoline stove to prepare a meal. It took a while to

melt the several million year old hard blue ice chipped from a nearby

glacier. Into the uncontaminated water went a combination of chicken,

spaghetti, beef, and everything else readily available to make the most

delicious 18 cups of 'hooch' any of us had ever tasted. Then we made

another try.

The pilots followed along the coast, hoping we

could stay close enough to the glacier fronts and rocky outcrops abutting

the sea to find our way back to McMurdo. But again, the curtain of white

dropped. In a flash reaction we made a sharp bank towards the last visible

crevasses at the edge of the ice barrier. As we jolted around 180 degrees,

I thought we were going to crash into the glacier front, but the skillful

pilot righted the craft and we returned again to Cape Royds.

By now we had seen more of the volcanic ash,

penguins and Shackleton's hut than we cared about. It was easy to conclude

we really didn't want to become heroes after all. Walking 40 miles back to

McMurdo was out of the question. In our path lay mountainous terrain

dotted with crevasse filled glaciers pouring down the valleys from Mt.

Erebus. Nor could we reach the base over the sea ice pierced with wide

open water leads quite impossible to cross. Our return depended solely

upon the two helicopters and our next try would have to be successful as

there was insufficient gas left for a third abortive attempt.

Left momentarily to our individual reveries, I

had no difficulty imagining the men of the top Command back at McMurdo

figuratively tearing their hair. Innocently enough, I had become a good

example of why, in those times, the U.S. Navy had to swallow hard each

time it permitted a woman to enter its once exclusive Antarctic domain.

Long ago, I had broken this tradition on my husband's 1946-48 private

expedition when I spent a year on the other side of the Continent. But,

now my safety was clearly the Navy's responsibility. Mentally, I cringed

at the sticky situation, and could only surmise the assessment that must

be taking place.

As time wore on, the dingy hut took on new

dimensions. In spite of a New Zealand Government notice cautioning all

visitors from removing any item whatsoever from the historic shrine, we

began to eye the corroded cans of Bird's Egg Powder, Cabbage, Ox Tongue,

weathered boxes of hard tack biscuits, and suspected bottles of brandy

with more than casual indifference. Only a musty bottle on the medical

shelf labeled as the remedy for diarrhea and dysentery provided the

necessary restraint.

Dirty torn socks, worn mukluks, inadequate

shoes, old blankets, well used pieces of canvass and unappealing seal

skins, covered with layers of volcanic dust had been fascinating testimony

to the hardships of long past era when we first arrived. Now, the longer

we remained the cleaner the surroundings appeared. Subconsciously, each of

us picked out a corner or niche on a hard bench which might possibly

afford some relative comfort during the forthcoming night. Every 30

minutes or so we had to move around to keep our circulation going. There

was a stove. Had there been fuel, a note indicating the old relic did not

function property dissuaded us from the probable fire hazard. Clearly, an

overnight experience under these conditions would separate "the men from

the boys."

Fortunately, no one was put to the ultimate

test. During one of our forays out for exercise, we noticed a small break

in the dense cloud cover. Slowly, the patch began to grow. We were

enthralled. When the sun finally broke through, eighteen elated visitors

bounded up the volcanic slag hill to the waiting helicopters without a

backward glance. Someone up there had delayed our moment of truth.

Forty-five minutes later we were thawing out in McMurdo's familiar

surroundings. The episode made a believer out of me. Never again did I go

further than the mess hall without taking my own survival gear.

My husband died in 1980, and although, I

continue to give spot lectures, as before, there was every reason to

believe my active Antarctic "career" was over. However, some twenty-three

years after having accompanying him to the Pole, I returned to the Base on

Stonington Island, Palmer Peninsula, where we had spent a year on the

Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition forty-seven years before. I was the

guest lecturer in February 1995 on Abercrombie and Kent's tourist cruise

ship Explorer. Their unpublicized objective was to get me back to our

Base, which had recently become the First American Historic Site in

Antarctica. Ice conditions being what they are in that area, I gave them a

thirty percent chance of penetrating the pack ice. We were unbelievably

lucky, and made it, within that year's two and a half week ice free span.

I had never expected to get back and gaze upon

that magnificent scenery again. But, what made it doubly thrilling, was

that my daughter, Karen Ronne Tupek, was with me, becoming the fourth

member of the Ronne family to visit the world's most spectacular

continent.

The trip reawakened and renewed my interest. I

am planning to return in January and February 1996, as a guest lecturer,

(along with Sir Edmund Hillary), when Orient Lines ship Marco Polo, will

semi-circumnavigate the continent from Palmer Peninsula to McMurdo Station

in the Ross Sea and from there to Christchurch, N.Z. Currently, I am

preparing a manuscript of my Antarctic experiences by utilizing my diary,

which graphically depicts my historic year there in 1947 - 48.

![[LINE]](http://205.174.118.254/nspt/lineshd.gif)

The following article appeared in The

Washington Post, April 5, 1995

Jackie Ronne's Return Trip to an Antarctic

Wasteland

by Judith Weinraub, Washington Post Staff

Writer

Women do things for love they might not do in

their right minds: Ignore infidelities. Raise other women's children. Rob

banks.

Edith "Jackie" Ronne spent 15 months in a

12-by-12 hut in Antarctica.

She went there in 1946, two years into her

marriage to a drop-dead handsome naval officer and explorer. Finn Ronne,

who had two previous polar expeditions to his credit, returned south after

World War II to survey the last unknown coastline in the world, a 650-mile

stretch along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Somehow, he talked his reluctant wife into

accompanying him on a six-week voyage to the land of icecaps, seals and

penguins.

"I was ready to do anything for him," says

Ronne of her husband, whose father, Martin Ronne, was also a polar

explorer.

In late February Jackie Ronne, 75, a widow

since 1980, extended the family saga by taking her daughter Karen on a

cruise to the base camp that housed her husband's expedition. Although

she'd been back to Antarctica, she hadn't seen the camp since they left in

the spring of 1948. "It's an extremely difficult place to get to," she

says. "The icy conditions make it hard. You have to hit it just right.

"I never thought I'd return," she says, for it

was more than the ice and cold that made life difficult -- so difficult,

in fact, that she'd never reread her Antarctica diaries.

Jackie and Finn Ronne (pronounced "Ronnie")

met on a blind date in wartime Washington. He was 42, Norwegian-born,

divorced, glamorous -- a man who had driven dog teams hundreds of miles

across the Antarctic, exploring uncharted sections of the continent. She

was 22, a George Washington University graduate living with her aunt and

uncle in Chevy Chase who bused downtown each day to a typing and filing

job at the State Department and worried that nothing exciting ever

happened to her.

She was making her way through the ranks when

friends matched the two up because they both skied -- though Jackie was

just starting and Finn was a competitive ski-jumper. They courted for a

year, hiking along the Appalachian Trail, biking when gasoline was scarce,

rolling back the rug and dancing on her aunt and uncle's highly polished

hardwood floors. March 18 would have been their 51st wedding anniversary.

When they married, Finn promised her he'd

never go back to the Antarctic. "Fortunately," says his widow, "I didn't

believe him."

The land -- with its earthquake shocks and

rocks, its trying temperatures -- was his obsession. And he wanted to

command his own expedition.

A trained geographer and naval engineer, Finn

Ronne began raising money as soon as the war was over, but it was a

struggle. And his former expedition leader, the renowned (and influential)

Adm. Richard E. Byrd -- by then a rival -- was not supportive. To this day

Jackie Ronne holds Byrd accountable for unexpected minefields her husband

encountered establishing the expedition, and for its shoestring budget of

$50,000. (He had originally hoped to raise $150,000.)

The dangers of the expedition were real: the

blizzards that could kill a man in an hour, the hidden crevasses, the

icebergs, the way the white landscape could trick the mind. But newspaper

stories about Ronne's plans prompted 1,100 volunteers. Ronne chose 21,

some with polar experience, some with much-needed flying, medical or

mechanical skills, others with a taste for adventure.

Jackie Ronne didn't share their daring. She

agreed to accompany the explorers to Beaumont, Tex., where their boat was

waiting, but that was it. "I was sad," she recalls. "I expected him to be

gone for 15 months, and I knew I would miss him tremendously, but I was

comfortable with the arrangement."

In Beaumont, Ronne persuaded her to stay with

the group until it got to Panama. But as the ship made its way down the

Chilean coast toward Cape Horn, Ronne urged his wife to commit to the

whole trip. Because English was not his first language, Ronne needed his

wife's help writing the articles he'd committed to for the North American

Newspaper Alliance, which had provided some funding.

Even now, almost 50 years later, she recalls

the arguments she made in a hotel room in Valparaiso -- the last place she

could change her mind.

"No woman had ever gone that far south, and

the crew was suspicious," she says. "And my family was very conservative.

They would never go after headlines. My aunt was frantic. . . . And I was

afraid that if I went with him, people would say he took me along for the

publicity.

"But he was very, very persistent."

When she finally decided to stay with him,

Jackie Ronne realized that all she had brought along to wear were cocktail

dresses and nylon stockings -- "everything I would have had for two weeks

in Texas."

So, in Punta Arenas, Chile, she disembarked to

purchase nightgowns, slippers and a robe, ski boots and general

necessities, plus knitting wool and needles to while away the evenings

during the long antarctic winter. (The Army Air Corps had supplied cold

weather clothing that it wanted tested.)

"I was in love with him," she says simply. "I

would have done anything to support the expedition, even stay behind. I

would have gone to the moon. It was the moon." Every night throughout the

15-month expedition, she recorded the day's activities and challenges --

and her own comments. She filled three notebooks -- the first in a

school-size copybook, the next two in ship's logs.

But until three months ago, when she began

preparations for her recent trip, she hadn't looked at the diary in 47

years. "I didn't want to be reminded of the pain," she says.

"I wasn't prepared for the bickering and

in-fighting," she says sadly. "People don't get along well in isolation."

The stresses of the expedition were apparent

almost immediately. In isolation, emotions festered, and without warning,

small disagreements became serious disputes. In particular, tensions

emerged with a young pilot and his new wife who was the second woman in

the group. "We never exchanged a harsh word," says Ronne now, "but there

was a period where we didn't speak at all."

The physical challenges were more

straightforward. Even though Finn Ronne headed for familiar territory, his

old base camp on Stonington Island, it was a demanding, stormy place, with

blinding winter blizzards and inaccessible, ice-packed harbors. And the

days were filled with difficulties and dangers.

Reaching Antarctica just before the winter

freeze, there was a great deal to do. The base was uninhabitable for

humans or dog teams without repairs. Supplies, including three small

planes, 100 55-gallon drums of high-octane gas and all their scientific

instruments, had to be unloaded and stored.

And after dark, there wasn't much to do except

play cards, watch movies, study navigation and worry.

"I was constantly worried," Ronne says. "The

Antarctic is a dangerous place. You can turn your back and find somebody

in great difficulty. The door to our hut was open 24 hours a day to report

emergency situations. . . . One of our men went down a crevasse and was

stuck upside down for 12 hours before help came. Until the rescue team got

back, nobody slept. Nobody thought he would ever come out alive. Finn was

beginning to worry about what he should do with the body."

Beyond the immediate challenges, the Ronnes'

underlying concern was the success of the expedition. "I was always

worried about it," she says. "But actually the tensions didn't affect it

very much. My husband had a firm hand over what was going on."

When the year was over, she was proud: proud

of the success of the expedition, proud to have been the first American

woman to set foot on the continent, proud that she and Finn were the first

couple to reach the South Pole and that she was the first non-royal woman

to have an Antarctic site -- an ice shelf -- named after her.

But she was glad to leave it behind. "When I

saw the Statue of Liberty on my return, I felt the same as any immigrant.

The sight was a relief and release to me." Jackie Ronne has lived quietly

since her husband's death, traveling, spending time with her family and

using her Antarctic expertise lecturing and writing encyclopedia articles.

The embassy dinners and parties disappeared immediately, of course. "But I

don't crave social Washington," she says. "I've been there."

Her home in Bethesda has the understated look

of a house designed to set off memorabilia. The framed photographs and

maps. A toy-size hickory sledge her husband made to pass the Antarctic

hours. A radiogram from Byrd asking him to join the admiral's second

expedition.

And penguins everywhere. Mounted and stuffed,

in the living room hall. On pendants and earrings. Potholders.

Refrigerator magnets. The shower curtain. "Most people don't even know

that penguins are from the southern hemisphere," she says.

She knew about Antarctic cruises but never

wanted to go on one until late last year when she was asked to plan "an

ultimate field trip" for a group of college scientists. The Society of

Women Geographers signed on too, and the Washington branch of the

Explorers' Club.

Ronne worked with the Chicago-based

Abercrombie & Kent agency, which regularly tours the area, to plan the

trip. Together with daughter Karen, 44, as the stars of a well-heeled

group of 92, a different Jackie Ronne set off than the explorer's young

wife -- an older woman who swims to stay in shape and delighted in finding

penguin rookeries and buying T-shirts for her grandchildren.

The journey was not for the faint-hearted. The

weather was just as difficult and the ice as treacherous. "The wind was

incredibly strong, a gale force," says Ann Hawthorne, a photographer and

family friend who was on the trip.

The access to the Stonington Island base was

just as unpredictable. "We had to get through pack ice to get in," says

Ronne. "But the captain and crew were determined to get me there."

Since their ship was too large to get through

the icy coastlines, land was reached by large, hard-to-maneuver rubber

rafts. When the rafts couldn't get any closer, the stalwart walked the

rest of the way, wearing several layers of clothing, parkas and high

boots. "And the clothes got really heavy when they got wet," says Ronne. Since their ship was too large to get through

the icy coastlines, land was reached by large, hard-to-maneuver rubber

rafts. When the rafts couldn't get any closer, the stalwart walked the

rest of the way, wearing several layers of clothing, parkas and high

boots. "And the clothes got really heavy when they got wet," says Ronne.

Her ultimate goal was the 1946 base camp and

the hut she had shared with her husband. Ronne was determined to show her

daughter where she'd spent those long months. As the two climbed the

100-yard hillside to the camp, they had to negotiate thigh-high snow, and

almost turned back. To propel them forward, Hawthorne told jokes when they

fell. Her ultimate goal was the 1946 base camp and

the hut she had shared with her husband. Ronne was determined to show her

daughter where she'd spent those long months. As the two climbed the

100-yard hillside to the camp, they had to negotiate thigh-high snow, and

almost turned back. To propel them forward, Hawthorne told jokes when they

fell.

"It was important to get Jackie to that base,"

she says. "It was a walk of discovery back in time."

Was Ronne reliving her life? "To a certain

extent," she says now, describing with dismay the uninhabitable buildings

she discovered. "When a base is left, it's legitimately considered

abandoned in the high seas. But I wanted to fix up what was broken, iced

over, ripped out. And I wondered what happened to our 5,000-pound galley

range and curtained bunks." And she hadn't anticipated the images of

"hurdles and vicissitudes" that she says came flooding back.

When Ronne left the camp a few hours later,

she closed the door firmly, shutting out the wind and snow and -- perhaps

-- some of her memories. "I wouldn't have given up that experience for a

million dollars," she says. "Nor would I ever have done it again."

But she just might take another cruise there.

One that heads on east into South Georgia tempts her. "There's something

about the Antarctic that draws you back," she says. "You might have had it

up to your eyebrows, but after a while, the raw, icy magnificence brings

you back."

Alternate Bios:

Edith "Jackie"

Ronne (b. 1919) was a U.S.

explorer of Antarctica.

She married Finn Ronne on March 18, 1941, and on the expedition of 1946 -

1948, that her husband commanded, she and Jennie Darlington, the wife of

the expedition's chief pilot, became the first women to over-winter in

Antarctica. They spent 15 months together with five other member of the

expedition in a small station they had set up on Stonington Island in

Marguerite Bay.

Edith Ronne Land was named after her by her husband, who discovered the

coastline and claimed the interior land as well. When it was

determined to be mostly ice shelf, the name was changed to Edith Ronne Ice

Shelf. At her request, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names removed

her first name, so that the Ronne Ice Shelf would more correspond to the

continent's other large ice shelf, the Ross Ice Shelf..

Edith Ronne returned several times to Antarctica, including on a

Navy-sponsored flight to the South Pole in 1971 to commemorate the 60th

anniversary of Roald Amundsen first reaching the South Pole (she was the

seventh woman at the pole), and a 1995 trip back to her former base at

Stonington Island as guest lecturer on the expedition cruise ship

Explorer. Edith Ronne returned several times to Antarctica, including on a

Navy-sponsored flight to the South Pole in 1971 to commemorate the 60th

anniversary of Roald Amundsen first reaching the South Pole (she was the

seventh woman at the pole), and a 1995 trip back to her former base at

Stonington Island as guest lecturer on the expedition cruise ship

Explorer.

Another Bio of Jackie, with

much about The Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition:

Edith (commonly known as “Jackie”) Ronne was

an important Antarctic explorer who was one of the first two women to

winter over in Antarctica. Her husband, Cdr. Finn Ronne, USNR, led the

Ronne Research Expedition (RARE) of 1947-48. This was “the last large

private expedition to Antarctica. It explored both coasts of the Antarctic

Peninsula and the Weddell Sea’s southern coast, both on the ground and

with three ski-equipped aircraft loaned by the U.S. Army Air Force.” [Jeff

Rubin, “A Rare Reunion,” The Polar Times, vol. 3 no. 6, January 2005, p.

4.]

Finn was Norwegian-born and educated, and already a veteran of two

Antarctic expeditions, including the second Byrd expedition and the U.S.

Antarctic Service Expedition. He was the son of Martin Ronne who,

as a sail maker on the Fram, had accompanied Amundsen to Antarctica, and

served with him for twenty years. Martin also took part in Byrd Antarctic

Expedition I [1928-1930].

Finn was a remarkably self-disciplined

man, well known for his lifelong excellent physical condition, and who had

skied all over the Antarctic continent. Finn and Jackie, a State

Department employee at the time, who graduated from George Washington

University in 1940, met in Washington, D.C. in 1942. They were married on

March 18, 1944. Finn was a remarkably self-disciplined

man, well known for his lifelong excellent physical condition, and who had

skied all over the Antarctic continent. Finn and Jackie, a State

Department employee at the time, who graduated from George Washington

University in 1940, met in Washington, D.C. in 1942. They were married on

March 18, 1944.

As soon

as WWII ended, Finn began planning another expedition. Admiral Richard E.

Byrd, a friend of Finn’s at the time, who lived only a block away, urged

Finn to join forces with him, but Finn insisted on his own independent,

private operation. Although Finn and Byrd had served together on the

United States Antarctic Service Expedition, 1939-41, Byrd did his utmost

to torpedo Finn’s plans for his independent venture. Byrd even demanded

that Finn give him all of his detailed plans, which reluctantly Finn did.

These were then presented as Byrd’s own plans for his own expedition;

according to Jackie not even the wording of the proposal was changed. It

seemed clear to Jackie that Finn’s erstwhile friend, Admiral Byrd, had

“double-crossed” him.

Despite Byrd’s strong opposition, there were still

many offers of help to Finn, including Sir George Hubert Wilkins, General

Curtis LeMay, Ed Sweeney, a long-time friend, the Office of Naval

Research, and Allen Scaife, of the wealthy Mellon family of Pittsburgh.

Although Byrd’s fierce opposition failed to stop Finn’s expedition, it did

succeed in limiting necessary funding. Less than $50,000 was raised, and

many participants were unpaid volunteers. Thanks to General LeMay, several

military personnel were “seconded” to the expedition, including the two

principal pilots. The Air Force also donated three planes, equipment,

spare parts, and clothing. As Finn worked constantly on planning his

expedition, Jackie’s initial role was to edit and type all of his

correspondence. At this same time, at the end of 1946, as he was

presenting his proposal, Finn also served on the Task Force that created

the Thule Air Force Base in Greenland, and he assisted Thor Heyerdahl in

planning his trip across the Pacific on a balsam raft.

The Ronne Antarctic

Research Expedition (RARE) departed for Antarctica from Beaumont, Texas,

on January 27, 1947. Among the key personnel were the pilots Harry

Darlington, Jimmy Lassiter and Lieutenant Chuck Adams, and the aerial

photographer, Bill Latady, who used a trimetrigon camera to capture a

horizon-to-horizon scan. There were three planes – a twin engine C-45

Beech, a Noordwyn C-64 Norseman, and a Stinson L-5. When one of the planes

was damaged beyond repair while loading, General LeMay found them an exact

match.

As she has recounted in her diary, which she kept every day of the

trip, Jackie originally had no intention of going to Antarctica with the

Expedition. Only the extreme persuasive powers of her husband, Finn,

ultimately persuaded her to go. Since his native language was Norwegian,

he needed her to write English-language articles for the North American

Newspaper Alliance. These were written under Finn’s name, and for a long

time the press was unaware that both she and her friend, Jenny Darlington,

were along. Both women faced strong opposition from their own family

members (Harry Darlington, the pilot, at first was adamant that his wife

should not go) and from some male crew members, who said they wanted no

women onboard. Ultimately most of the men were supportive. One original

doubter, Chuck Hassage, became Jackie’s life long friend.

The final

decision for the women to continue on to Antarctica was made in

Valparaiso, Chile, where they purchased some essential clothing items

including boots. A total stranger gave Jackie knitting needles that she

used frequently; in fact, some of her knitting made with those needles is

on display in the Naval Museum. The last port of call was Punta Arenas

where the sea proved to be surprisingly calm even as they crossed Drake

Lake. Walter Smith was the navigator, and always did an excellent job.

Jackie’s first approach to Antarctica was incredible, the “experience of a

lifetime.” The ship anchored alongside the Antarctic (Palmer) Peninsula

right in front of the British base built there during the war.

After some

initial awkward interactions, the British soon became good friends, and

the British commander, Ken Butler, spent many congenial evenings in the Ronne’s hut. Other prominent British participants were Kevin Walton,

Charles Swithenbank, and Bernard Stonehouse. The latter was one of three

British men rescued by pilots Lassiter and Adams after their plane, a

small Auster, crashed on the Weddell Sea coast.

The role of the airplanes

was of the utmost important to the Expedition. Unfortunately the weather

was usually difficult or unpredictable. During the whole time the flying

season took place, there were only eight good flying days. Peterson and

Bob Dodson traveled by dog team to the upper plateau to establish a

weather station to support the planes. While there, Peterson fell in a

crevasse, but Dodson was able to ski back to the base for help. A search

party was organized immediately in the dark. The British doctor, Budson,

not only volunteered to go, but later was lowered into the crevasse to

rescue Peterson who, incredibly, was still alive. He had been lodged

upside down in the crevasse for twelve hours. His recovery was complete,

but Finn was furious with both men since their disregard for rules of

safety had led to this costly misfortune. The men were not roped properly,

their sleeping bags were soaked, and Peterson stepped on the radio key and

broke it. Both were largely confined to the island base for the remainder

of the Expedition.

Another potential disaster was narrowly averted when

[?] McClary fell off a 150 foot ice cliff, and through thin ice into the

water. Fortunately, help was nearby and he was pulled to safety. Later he

suffered a broken collarbone in a sledding accident.

Jackie spent most of

her time in the 12 square foot hut she shared with Finn, although she

usually ate her meals with the group. There were no private toilet

facilities for women. All had to visit the “little house on the hill” no

matter what the weather. All of the men acted always as “perfect

gentlemen” in the presence of Jackie and Jenny Darlington. She experienced

a great deal of tension as “everything that happened worried me.” She

vowed, “I will never, never go to the Antarctic again,” but recently she

finished her thirteenth trip there.

Over time, tension developed between

Finn and Harry Darlington. Harry was third in command behind Finn and Ike Schlossback. Initially a close personal friend, Harry reportedly was

undermining Finn behind his back. On several occasions Harry entered

Finn’s tent “screaming” about the dangers of the flights he had been

assigned. Finally, Finn could tolerate no more such insubordination, and

dismissed him. Lassiter and Adams took over Darlington’s assignments. The

two pilots never had any accidents or trouble, scouted unknown territory,

and earned commendations from the Air Force. Ike Schlossback also wanted

to fly. He was a trained pilot who had commanded surface vessels,

underwater vessels, and a flight squadron, and was the only person in the

Navy at the time who had done all three. But he only had one eye, and Finn

never allowed him to take a plane up.

Harry was never reinstated despite

pleas from certain friends, and later complained to Finn about the several

short flights that Jackie made as a passenger. Jenny tried unsuccessfully

to smooth things over with Finn and Harry. After the weather station had

been established on the other side of the 6,000 foot-high plateau, an

advance base at Cape Keeler was created. It was mainly an underground

base, covered by snow, and connected by tunnels, but there was a command

tent on the surface. There were caves going out from tent where people

could stay with sleeping bags.

Two planes, the Norseman and the Beechcraft,

departed south from Cape Keeler on exploring missions in the rare

intervals of good flying weather. On one such flight Finn discovered

Berkner Island, in the middle of the later-named Ronne Ice Shelf.

Dog

teams were never flown into the field, although occasionally a sick dog

was flown back to base. The Chief Geologist, Bob Nichols, led a

fifteen-dog team that gathered rocks, did glaciology, measured solar

radiation and atmospheric refraction, and operated a cosmic ray machine.

His party spent 105 days in the field. This broke the previous record of

84 days for a sledging trip set by Finn and Carl Eklund seven years

earlier. Finn became irritated when Nichol’s party did not keep regular

radio contact.

Jackie developed a personal interest in science, and she

worked as an assistant to Andy Thompson, a seismologist, who measured the

first earthquake recorded in Antarctica, and recorded tides.

In February

1948, as warmer weather returned to Antarctica, and the sea ice began to

melt, preparations for departure from Stonington Island were made.

Gasoline supplies were low, and the flying program was over. The year in

Antarctica had come to an end. An icebreaker cleared a path to the open

sea. Rough seas hampered the trip northward, and food was running low. It

was necessary to make an unscheduled stop in Punta Arenas. Here Jackie

enjoyed her first fresh salads and vegetables in some months.

Jenny

Darlington was pregnant, and she and Harry flew home from there. The ship

proceeded up the west coast of South America, through the Panama Canal,

and on to New York. Here the American Geographical Society hosted by Sir

George Hubert Wilkins honored the party. Lincoln Ellsworth was also

present. It was a wonderful occasion, but even so Jackie said

emphatically, “I will never, never, never go back to the Antarctic.”

But

the lure proved irresistible, and she returned many times. She was a

passenger on the first tourist cruise ever to the Antarctic. The ship

visited Deception Island and an Argentine base. In 1971, Jackie and Finn

were flown to the South Pole in Navy planes. A base, including the South

Pole Dome, was under construction there, and Jackie and Finn made a radio

broadcast to Lowell Thomas directly from the pole.

In 1995, as a lecturer

on the Explorer, she and her daughter, Karen, visited the old base from

the RARE expedition. Nothing was left. It was totally empty. Everything

had been stolen by various nationalities coming down. Even the 300-pound

cooking range was gone. Later the National Science Foundation sent Mike Parfit to restore and preserve the base. Jackie returned a year later, but

once again everything was stolen. “It was sad to see how the base had

changed, and how everything had been stolen from it.”

In recent years,

Jackie has continued to lecture on the Explorer and the Marco Polo. Finn

was the leader of the first Lindblad tourist cruises to Antarctica.

Reflecting on her long association with the Antarctic, Jackie is thankful

for her first trip in 1947-48, one that created all sorts of later

opportunities. “It made my life.”

She has since traveled and lectured

throughout the world. “The Ronne expedition achieved a great deal,

exploring more than 250,000 square miles of Antarctica. By overflying the

Antarctic continent’s, and the world’s, last major stretch of unexplored

coast, along the Weddell Sea from the Antarctic Peninsula to Coats Land,

the expedition determined that the Weddell and Ross Seas were not

connected. In 346 hours of flight time, including 86 landings in the

field, RARE took nearly 14,000 photographs covering 450,000 square miles.”

[Jeff Rubin, The Polar Times, vol. 3 no. 6, January 2005, p. 4.]

From

Society of Woman Geographers:

Wooster College,

1936 38. BA, George Washington University 1940, History and English.

Ronne was the first woman to set foot on the continent of Antarctica and

stay, when she wintered-over there in 1947 48 as a member of her husband

Finn Ronne's Antarctic Research Expedition at East Base on Stonington

Island. The interview describes her family background, childhood,

education, and activities after her Antarctic experience, but the bulk of

the interview provides a detailed personal account of the expedition, its

planning and preparation and various personalities, including Admiral

Richard Byrd, who were involved in one way or another. Her account also

refers to other historical events involving Antarctica and polar

exploration. Member Explorers Club. Joined SWG 1948. Carried SWG flag to

the South Pole in 1971 for celebration of 60th anniversary of Amundsen's

reaching the pole. SWG President 1978 1981.

Jackie is

featured on an "Adventures

of the Elements" game card:

Human Guardian

Born Edith Anna Maslin on October 13, 1919, Jackie was riased in a